Caesar returns to Rome

In 49 BC C. Julius Caesar crosses the Rubicon River, marking the beginning of the second civil war of the Roman Republic.

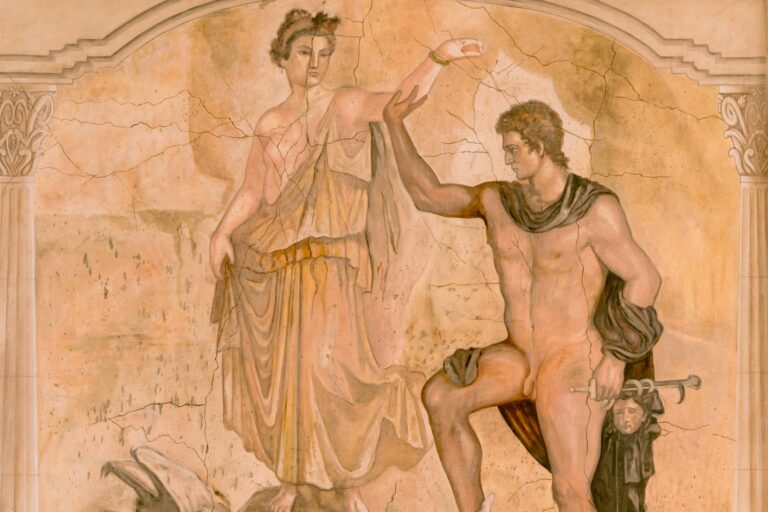

This artwork, by the famous french artist Adolphe Yvon, shows Gaius Julius Caesar illegally returning to Italy from Gaul, which is considered the trigger or casus belli of the Second Civil War, which in turn ended up undermining the already weak foundations of the Republic, later giving way to the rise of the Empire at the hands of his adopted son Octavian.

Knowing that, the painting has many interesting details. Caesar is depicted by the artist with the world in his hand, and crowned with the laurels of victory. Not too subtle. With him come misery and death, which almost always accompanied his army, as during the brutal Gallic war (which, according to Caesar himself, claimed the lives of more than a million people).

Some people will say that Caesar waged a war of extermination, but it is necessary to remember that those were different times, when the value of human life was not measured as it is today and when the annihilation of a nation could be considered a common consequence of wars.

Below Caesar are his roman rivals (or Gaul). He advances impassively toward them, seemingly unconcerned about anything. Behind him, tied by the neck to his horse’s tail, is a group of prisoners. This may have been deliberately emphasized by the French artist; indeed, during his wars, Caesar regularly forgave his roman enemies, although his reasons may have been more publicity-driven than virtuous. Caesar liked to present himself as just. However, he didn’t routinely show the same clemency to the Gauls. Two examples: he himself claimed that, after defeating the Usipetes and Tencteri, he attacked their undefended camp and massacred all the men, women, and children, to the tune of 430,000 (a highly exaggerated figure). And, after capturing Uxelodunus, he ordered cut he hands of all the surviving defenders.

On the horizon, Caesar’s journey is portrayed as apocalyptic; destruction, fire, and smoke accompany an allegory of death as it points Caesar toward his homeland. At first glance, this painting could portray Caesar as a divine figure. However, the closer you look, the more sinister it appears. It should come as no surprise that the artist is French, so it’s clear that this is a condemnation of the Gallic Wars.

Caesar described his campaign as a preventive and defensive action, but historians agree that he started these wars primarily to advance his political career and pay off his debts.

Since assuming government over the provinces of Cisalpine Gaul and Transalpine, he intentionally sought to intervene in the affairs of the various Gallic tribes with the aim of seizing control of the entire country. In pursuit of this goal, he didn’t hesitate to destroy villages and towns and enslave hundreds of thousands. He and his army were absolutely brutal toward the Gauls who opposed him, and it is certain that, despite later granting them roman citizenship and even bringing some Gallic nobles into the Senate, the resentment of the population was deep, but their fear was even more so.

For ten years, he ravaged the Gallic territory, now French. But it’s worth noting that the conquest of Gaul, in addition to preventing the advance of the even more fearsome Germanic tribes at the time, ensured Rome’s survival for the next five centuries and also allowed it to spread its culture to almost every corner of Western Europe, a culture of which we are also heirs.